Welcoming Ourselves Home

We seek to plant seeds of contextual understanding and of a vision for a more beautiful world. To help see with honest eyes and clear vision the web of life that we are all part of. In this tapestry of belonging we are all one on the same earth. Connected through our relations, we are the earth and the earth is our body.

This area of our curriculum is focused on fundamentally reimagining ourselves, our society’s foundational systems, the structure of our relationships with each other and the natural world. It covers competing ecological philosophies or ecosophies, ways of reconnecting, and visions of fairer and better systems.

“Sitting at our back doorsteps, all we need to live a good life lies about us. Sun, wind, people, buildings, stones, sea, birds and plants surround us. Cooperation with all these things brings harmony, opposition to them brings disaster and chaos.”

– Bill Mollison

Topics

Sacred Economics

Becoming Native

Deep Ecology

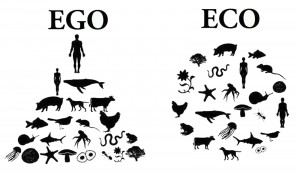

Deep Ecology is an environmental philosophy (ecosophy) and social movement first labeled with the phrase Deep Ecology by Norwegian philosopher and mountaineer Arne Naess in 1972. Unlike “the shallow ecology movement,” he envisioned a “long-range deep ecology movement” that was underway at the grassroots level.

This movement looked deeper and more philosophically, questioning root causes and basic societal assumptions. It deals with not just how to protect the environment, but why.

“The Shallow Ecology movement: Fight against pollution and resource depletion. Central objective: the health and affluence of people in the developed countries.”

“There are deeper concerns which touch upon principles of diversity, complexity, autonomy, decentralization, symbiosis, egalitarianism, and classlessness.”

-Arne Naess in The Shallow and the Deep,

Long-Range Ecology Movement, A Summary.

Naess gave this grassroots movement a name. Later he and American environmentalist George Sessions set forth a platform of eight principles that they felt characterized the movement. The platform begins by accepting that all beings and the earth itself have intrinsic value independent of their usefulness for human purposes.

Naess also noted that the richness and diversity of life forms contributed to the realization of this intrinsic value. The rest of the platform builds on those concepts and provides guidance for humans to protect this richness and diversity.

Deep Ecology says that humans must radically change their relationships with nature, oppose destructive industrial technology, promote ecological agriculture, and foster diversity of culture.

“We are called to assist the Earth to heal her wounds and in the process heal our own—indeed to embrace the whole of creation in all its diversity, beauty, and wonder.”

– Wangari Maathai

The Work That Reconnects

The Work That Reconnects is a pioneering practice dating back to the 1970’s and based on the teachings of Joanna Macy. Originally called Despair and Empowerment Work, Macy later encountered the work of Arne Naess and John Seed. She acknowledged their work as part of the Deep Ecology tradition. She later renamed her work to “The Work that Reconnects” when academic disputes roiled the Deep Ecology movement.

The Work That Reconnects is an individual and group practice for reconnecting with the web of life, meeting the challenges of modern society, and moving forward with a hopeful activist heart. This work is realized as a four stage spiral: Coming from Gratitude; Honoring our Pain for the World; Seeing with New/Ancient Eyes; and Going Forth.

“If the world is to be healed through human efforts, I am convinced it will be by ordinary people, people whose love for this life is even greater than their fear.”

– Joanna R. Macy

This spiral may unfold over time spans large and small, and participants can come back to it repeatedly for overcoming despair, gaining new perspectives, and receiving inspiration, courage and clarity. The work is especially effective practiced in a group workshop led by an experienced facilitator. Many thousands of people have joined in the work over the past several decades.

Joanna Macy, the “root teacher” of The Work That Reconnects, earned a Ph.D. in Religion in 1978 at Syracuse University after studying at Lycée Français de New York, Wellesley College, and the University de Bordeaux. Her website notes that five years in Nigeria, Tunisia and India during her husband’s deployment as a Peace Corps director were a particularly formative experience.

The work is a powerful force for healing and inspiring activism. We are grateful to have experienced facilitators of the work living alongside us at Earthaven Ecovillage and offering this gift here during workshops.

“We must recover the sense of the majesty of the creation and the ability to be worshipful in its presence. For it is only on the condition of humility and reverence before the world that our species will be able to remain in it.”

– Wendell Berry

The Great Turning

The Great Turning is a term that is widely used to refer to a societal awakening to a new era of environmental restoration, justice, equality, and social cohesion. It is a hopeful opportunity for forming a new human collective consciousness that stands as a counterpoint to our current culture of destructive global corpocracy. Many writers have discussed the need for an epic human turning of this manner, using a variety of terms.

Craig Schindler and Gary Lapid first used the term The Great Turning in describing the work of Project Victory, which they founded in 1985 initially focused on reducing the risk of nuclear war. In 1989, they published The Great Turning: Personal Peace – Global Victory. Joanna Macy went on to further develop the concept, and introduced the term to large audiences through her writings and activism.

Though popularized by Macy, she reportedly sees it as a public term to be used by all and owned by none.

“In the past, changing the self and changing the world were often regarded as separate endeavors and viewed in either-or terms. But in the story of the Great Turning, they are recognized as mutually reinforcing and essential to one another.”

– Joanna Macy & Chris Johnstone, Active Hope

In that spirit, and based in part on his interactions with Macy at a series of State of the Possible retreats organized by YES! Magazine, author and activist David Korten released in 2006 his book The Great Turning: From Empire to Earth Community. His particular focus was on the destructiveness of Empire, incarnate today not as sprawling political structures but as global corporations with more power than governments.

Korten and others envision a societal unravelling based on the rapidly developing crises of economic imbalance, climate change, and peak oil. This collapse is clearly and increasingly visible in recent events around the world… Economic disruption from historically massive wildfires, floods, and hurricanes. Drought-sparked conflicts in the Middle East drawing in world powers to fight proxy wars. Snowballing civil unrest based on abusive power structures in the United States.

In this world view, an epic opportunity looms against the backdrop of our dystopian experience. Humans have the ability to undo the evils that have led to injustice, environmental damage, and inequality on staggering global scales. The challenge, as Korten frames it, is to realize a shift from “Empire” to “Earth Community.” To work toward sustainable & just communities, with local scale economies, marked by caring & mutual aid. His book serves as a stark warning but with an inspiring roadmap for The Great Turning.

Here at Earthaven Ecovillage, we are a living laboratory in working towards the turning, with over 29 years of experience in what works and what doesn’t in village living. And it is to share this learning and help bring about the turning that our residents have created SOIL.

“Demagogues direct our frustrations against other groups, blaming those most victimized. For the failures of corporate capitalism, we scapegoat each other.”

– Joanna Macy, in Coming Back to Life.

The Great Turning Resources

- Yes! Magazine for a periodic dose of “solutions journalism” and excellent teacher resources

- Living Economics Forum offers much detailed information & ideas that is well organized

- Our annual Earthaven Ecovillage Experience Week offer an immersive experience of the future

- Our Earthaven Ecovillage Experience Weekends offer a weekend experience

Ecofeminism

Ecofeminism is a diverse movement with multiple branches and their different positions and concerns. The broader movement is unified by the core insight that both women and the natural world have been victimized and exploited by now-dominant patriarchal societies. This perspective provides a foundation for both the analysis and practice of eco-feminism. It is a lens through which to look at environmentalism.

“Women must see that there can be no liberation for them and no solution to the ecological crisis within a society whose fundamental model of relationships continues to be one of domination. They must unite the demands of the women’s movement with those of the ecological movement to envision a radical reshaping of the basic socioeconomic relations and the underlying values of this [modern industrial] society.”

– Rosemary Radford Ruether, a founding ecofeminist

Most ecofeminists see a strong connection between women and nature. Cultural ecofeminists see this connection as biologically or psychologically intrinsic, with women closer to nature than men. They see a special and useful relationship between women and nature that makes women better able to take action to protect nature.

Other ecofeminists don’t see this link as natural and empowering. They view the connection between women and nature purely as a cultural artifact imposed degradingly by the patriarchy. This branch may be referred to as radical ecofeminism. And materialist ecofeminists embrace both perspectives.

There has been rich academic debate for decades between these branches, and it is hard to summarize in just a few paragraphs. As well, the labels for the branches seem debatable and are not applied consistently in the literature. Some might refer to cultural ecofeminists also as the radical branch, while our representation made above is more frequently seen as the radical.

“We see the devastation of the earth and her beings by the corporate warriors, and the threat of nuclear annihilation by the military warriors, as feminist concerns. It is the masculinist mentality which would deny us our right to our own bodies and our own sexuality, and which depends on multiple systems of dominance and state power to have its way.”

– Ynestra King

Another practical observation is that women’s interactions with environmental damage, particularly in less-developed areas, tend to be deeper or more relevant. This is due to their role as gathers of food and water which makes them more impacted day to day. Women are also more vulnerable to environmental damage because they are simply more vulnerable in general in patriarchal society.

Ecofeminists generally disagree with a core goal that many contemporary feminists have, which is to get more women into positions of power in the hierarchy. Ecofeminists are generally more oriented towards taking apart the hierarchy and distributing power more downward and more locally, so that people can make decisions about and live with nature in greater harmony.

One ecofeminist leader who really calls to us here at SOIL is Vandana Shiva. She is particularly focused on the damages of current large-scale, non-sustainable agricultural practices such as monoculture, GMO crops, and chemical use. She created the Research Foundation for Science, Technology and Natural Resource Policy in 1982 to develop and advocate for sustainable methods of agriculture. She has also published many books, and we find her writing to be powerful.

“We are either going to have a future where women lead the way to make peace with the Earth or we are not going to have a human future at all.”

– Vandana Shiva

Ecofeminism Resources

- Vandana Shiva’s 1993 book Ecofeminism written with Maria Mies

- Women and Nature? Beyond Dualism in Gender, Body and Environment presents more recent thinking in the field

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy’s extensive survey